Monday, November 24, 2014

Twenty Years of Johnny Cash Covering Edna St. Vincent Millay's Poem "The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver"

"I feel sure you will agree that the talents of Johnny Cash are well suited to a recording of 'The Harp Weaver,' and that the recording which I am enclosing is a dignified one," Starr writes. "As I told you in our telephone conversation, we would like to make an agreement for 'The Harp Weaver' as a musical composition upon the customary royalties of four cents per copy and 50% of the mechanical fees for records manufactures and sold of recordings of this song."

As we soon discovered, the P&PC office interns knew only the Johnny Cash of the iconic upraised middle finger and the cover of "Hurt" by Nine Inch Nails, so we sent them on a scavenger hunt for Cash's softer side. Here—nearly twenty years of Cash reciting "Harp Weaver"—is what they found.

1960 1970 1979

Friday, October 3, 2014

In D.C. with Edna St. Vincent Millay, Langston Hughes, and the Writers' War Board

So, here's the gist of our research. During World War II, the Office of War Information operated an outfit called the Writers' War Board, which was charged with recruiting American writers of all stripes for domestic propaganda efforts. Poets. Playwrights. Fiction writers. Journalists. Editors. Radio writers. Speech writers. Song writers. Cartoonists. Screenwriters. You get the idea. A propaganda campaign of one sort or the other—More Nurses Needed! Conserve Oil and Gas! Use V-Mail! Don't Waste Food! Join the Merchant Marines!—would come down the pike, and the WWB would find writers to help make it go. Need a fifteen-minute radio play pitching the way your average American can contribute to the war effort? Well, the WWB's got not just one but fifteen for you to choose from. But get this. Not all writers working for the WWB wrote explicit propaganda. The WWB archives show that office staff wrote to poets and pulp writers encouraging them to take up particular topics that would tie in with—and thus bolster the credibility and appeal of—current campaigns. When the WWB was tasked with encouraging Americans to do volunteer work on farms and orchards and thus increase food supplies, for example, it wrote to Berton Braley, Ira Gershwin, Edgar Guest, Oscar Hammerstein, Phyllis McGinley, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Ogden Nash, Cole Porter, E.B. White and others asking them to write about food and farming. "Will you spare the time," the WWB asked, "to turn out something on the joys of farm labor, of what you get from working with the green growing things of earth?"

P&PC has a specific story it's looking for—the story behind Edna St. Vincent Millay's long poem The Murder of Lidice that Millay wrote at the bequest of the WWB, that was published (in two different abridged forms) in the Saturday Review of Literature and Life magazine, that was broadcast nationally on NBC radio and translated into Spanish and Portuguese for shortwave broadcast to Europe and South America, that was issued in "pamphlet" form by Millay's publisher Harper & Brothers, and that was eventually put on vinyl as part of a three-disc set. After a week of looking through the WWB archives and Millay's own papers, we've now got scads of material to return home with and coax into some sort of coherent, white-knuckle story of how The Murder of Lidice came into being and unexpectedly went on to became what might have been up to that point the most widely circulated American poem of the century. Stay tuned, dear readers. You likely haven't heard the last from us on this topic.

As you can imagine, though, we're running across all sorts of other goodies. When the WWB wrote to George Bernard Shaw asking him to join the "Lidice Lives" campaign for which Millay wrote her poem, he replied, "No. I am not such a mischievous fool as to waste time in preserving the memory of atrocities of which we are all equally guilty." There are materials pertaining to Thurgood Marshall (then at the NAACP), Margaret Mead, Upton Sinclair, Archibald MacLeish, Arthur Miller, H.L. Mencken, Bernard Malamud, and more. One of our favorites? The letter from Langston Hughes pictured here. Based on what we've seen in the WWB archives, we think that by the time he wrote this, Hughes had been involved with the WWB in other capacities as well, as he's listed as author of two radio plays ("Brothers" and "In the Service of My Country") in a lot of fifty such plays being circulated at one point by the WWB. (Other plays, btw, were contributed by Stephen Vincent Benet, Margaret Sangster, and Pearl Buck.) We love the idea that Hughes was collaborating with W.C. Handy, and wouldn't you have loved to have been there when the Benny Goodman Quintet introduced the "Go-and-Get-the-Enemy-Blues" and Jimmy Rushing of the Count Basie Band let 'er rip?

It's an interesting little letter, too, isn't it? Consider how Hughes makes sure that the WWB's Clifton Fadiman knows the difference between a concert baritone and a blues singer. Even more interesting is how Hughes skews the letter away from the subject of race and toward both "folk" and U.S. national identities. Indeed, he mentions the "folk quality" of Joe Turner in paragraph one, and the "folk manner" of "That Eagle" which he pitches to Fadiman in paragraph two. And is that "Theme for English B" we hear echoing in the background of the second paragraph? Whereas "Theme for English B" (which wouldn't be written until after the war, we believe) concludes

As I learn from you,the rhetoric in this letter focuses on "how that eagle of the U.S.A. has got his wings over you and me." The poem makes race a constitutive part of the relationship between "you" and "me," but, as with Hughes's use of "folk," the letter to Fadiman elides explicit mention of race in favor of an American folk identity as the common ground of the WW II effort.

I guess you learn from me—

although you're older—and white—

and somewhat more free

Of course, Hughes's willingness to contribute to the WWB can't but be made ironic by the fact that over a decade later (in 1953), Hughes would be called to testify before Senator Joseph McCarthy—testimony that Hughes began with the sentence, "I was born a Negro." As we all know, Hughes's interest in communism stemmed in part from the color-blind view of the world it promised—a color blindness that Hughes also imagines in his letter to Fadiman about the "folk-ness" of American identity out of which his song lyrics emerge and to which they appeal. As the beginning of Hughes's speech before the Senate suggests, the crime Hughes was called to account for may not in fact have been his affiliation with communism but of imagining a color blind America. Indeed, in his speech to McCarthy's Senate subcommittee, Hughes doesn't begin by explaining his connection to the WWB or his activities working on behalf of U.S. interests in WW II—both of which could have been used (in theory) to demonstrate his red-blooded American-ness. Rather, he begins ("I was born a Negro") by acknowledging race as central to American identity, inserting himself back into the dominant rubric of American culture and effectively renouncing or repudiating his former views, his dreams of a color-blind nation.

At 73,000 items, the WWB Archives are pretty huge. They're disorganized. They're sometimes mislabeled. But we think that for people interested in the role of the writer working on what the WWB sometimes called the second cultural front during WWII, they're just waiting for someone with less of a targeted agenda than P&PC has to come along and make something big out of 'em. We'll be back here for certain, as there's more about Millay to explain. But who knows what other stories are also waiting to be told?

Tuesday, February 12, 2013

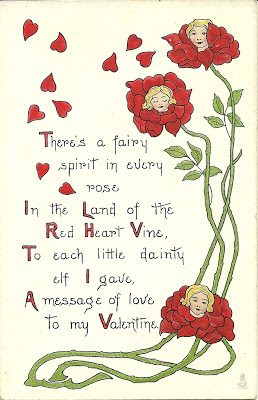

If the Great Poets Wrote Valentine's Day Verse: More Vintage Valentines from P&PC

Paul Laurence Dunbar:

Monday, May 24, 2010

Fiske Matters: P&PC Goes on Tour

In early June, the Poetry & Popular Culture office will be sending a delegate to Fiske Matters: A Conference on John Fiske's Continuing Legacy for Cultural Studies, which is taking place in Madison, Wisconsin, June 11-12.

In early June, the Poetry & Popular Culture office will be sending a delegate to Fiske Matters: A Conference on John Fiske's Continuing Legacy for Cultural Studies, which is taking place in Madison, Wisconsin, June 11-12.Our delegate will team up with three other scholars—two of whom you've met at this site before: Catherine Keyser, who in 2009 wrote about lingerie, nursery rhymes, and the new woman, and Melissa Girard, who recently weighed in on the cultural politics of slam poetry—for a panel cryptically titled "Poetry & Popular Culture":

Here is a preview of that panel:

Panel Overview

Panel OverviewLinking poetry studies and popular culture studies is not the most intuitive scholarly move, as the two fields rarely seem to overlap and even, at times, appear to have an openly hostile relationship with each other. In the most extreme cases, poetry is presented as an antidote to a debased low or popular culture, and popular culture is offered as a democratic cure to the cartooned elitism of poetry and high culture. However, as we hope to show in this panel, the two fields can do more than simply oppose each other; pairing them can be a provocative and productive endeavor that sheds light on and expands the histories and purviews of both in challenging ways. Indeed, in some cases, poetry is not just a relay point or magnifying glass for issues central to popular culture studies—the culture industries, celebrity, usability, audience participation, reception, etc.—but is a ground upon which popular culture was in fact built.

Poetry has intersected with every medium and facet of popular culture from Hallmark to Hollywood and Vanity Fair to Paris Hilton, and yet, because it is attributed a distinctive identity as a seat of genuine expression, it remains at the same time somewhat separate—a uniquely commodified moment when commodification supposedly gives way to uncommodified utterance. As a historically active site of popular activity, and as a singular discourse within that activity, poetry would seem to be a productive site of critical investigation for scholars of poetry and popular culture alike. This panel offers four examples of what that investigation might look like, each of which draws inspiration for its focus or method from John Fiske’s writing and/or critical legacy.

Poetry has intersected with every medium and facet of popular culture from Hallmark to Hollywood and Vanity Fair to Paris Hilton, and yet, because it is attributed a distinctive identity as a seat of genuine expression, it remains at the same time somewhat separate—a uniquely commodified moment when commodification supposedly gives way to uncommodified utterance. As a historically active site of popular activity, and as a singular discourse within that activity, poetry would seem to be a productive site of critical investigation for scholars of poetry and popular culture alike. This panel offers four examples of what that investigation might look like, each of which draws inspiration for its focus or method from John Fiske’s writing and/or critical legacy. 1) The Arbiters of Paste: Poetry Scrapbooking and Participatory Culture

1) The Arbiters of Paste: Poetry Scrapbooking and Participatory Culture by Poetry & Popular Culture

John Fiske defined “popular culture” as that culture which “is made by the people at the interface between the products of the culture industries and everyday life.” One of the central challenges that scholars face is in assessing popular culture in this formulation is amassing evidence of that interface—measuring and recording the types of activities consumers actually do, as well as the various ways that audiences transform the largely homogenized materials of mass culture in the course of everyday life. In this paper, I want to present a largely unknown archive of poetry scrapbooks which offers a material record of this process: evidence of how readers in the first half of the twentieth century artistically and critically repurposed mass-produced poems in large albums of verse that not only served as their age’s version of the mix tape, but that helped establish some of the dynamics of participatory culture that mark popular activity today.

Of particular concern to me is the relationship between ideology and resistance in the activity of poetry scrapbooking. On the one hand, in compiling their personal poetry anthologies, people were encouraged to imagine the activity as an accumulation of literary property that led to middlebrow cultural legitimacy; in fact, the textual act of keeping an album was regularly couched in terms of maintaining and keeping a house—both practices that fostered and relied on the centrality of the bourgeois self. At the same time, given the license to repurpose mass-produced poems, readers constructed albums that empowered critical thinking and challenged social conventions in any number of ways. This is especially the case with albums assembled by women readers, who found in their anthologies a freedom and privacy—a room of their own, as it were—in which to experiment with and explore the new subject positions of modernity.

Of particular concern to me is the relationship between ideology and resistance in the activity of poetry scrapbooking. On the one hand, in compiling their personal poetry anthologies, people were encouraged to imagine the activity as an accumulation of literary property that led to middlebrow cultural legitimacy; in fact, the textual act of keeping an album was regularly couched in terms of maintaining and keeping a house—both practices that fostered and relied on the centrality of the bourgeois self. At the same time, given the license to repurpose mass-produced poems, readers constructed albums that empowered critical thinking and challenged social conventions in any number of ways. This is especially the case with albums assembled by women readers, who found in their anthologies a freedom and privacy—a room of their own, as it were—in which to experiment with and explore the new subject positions of modernity. 2) Light Verse, Magazines, and Celebrity: Edna St. Vincent Millay and Dorothy Parker

2) Light Verse, Magazines, and Celebrity: Edna St. Vincent Millay and Dorothy Parker by Catherine Keyser

University of South Carolina

In 1928, Time magazine observed that “for ten years, smart young women have been trying to rival with their versification Edna St. Vincent Millay.” This comment connects reader and poet, public and celebrity, as both use poetry as an emblem of public self-fashioning. John Fiske addressed the contemporary female celebrity and her sexualized body in his essay on Madonna in Reading Popular Culture (1989). The contradictions he recognized in Madonna, a celebrity whose persona conveys both objecthood and agency, resemble the ambiguities that cultural historians trace in the flapper. Emulating Fiske’s attention to traces of domination and resistance in the presentation and reception of celebrities, I analyze poets Edna St. Vincent Millay and Dorothy Parker as emblems of modern womanhood within mass-market magazines.

With women moving into cities and entering the professions at unprecedented rates, Millay’s light verse about sexuality and mobility became enormously popular in the 1920s. Dorothy Parker cited Millay’s influence on her own career, claiming that she had been “following in the exquisite footsteps of Edna St. Vincent Millay, unhappily in my own horrible sneakers.” This language of “exquisite”-ness also suggests the vexed link between body image, fashion choices, and professional autonomy in the magazine fantasy of the urbane modern woman. I examine two magazines, Vanity Fair and the New Yorker, that provided readers with a vision of modernity and class mobility. Both magazines featured rhetoric prizing smartness, graphics promising luxury, and light verse presenting sexuality and femininity.

With women moving into cities and entering the professions at unprecedented rates, Millay’s light verse about sexuality and mobility became enormously popular in the 1920s. Dorothy Parker cited Millay’s influence on her own career, claiming that she had been “following in the exquisite footsteps of Edna St. Vincent Millay, unhappily in my own horrible sneakers.” This language of “exquisite”-ness also suggests the vexed link between body image, fashion choices, and professional autonomy in the magazine fantasy of the urbane modern woman. I examine two magazines, Vanity Fair and the New Yorker, that provided readers with a vision of modernity and class mobility. Both magazines featured rhetoric prizing smartness, graphics promising luxury, and light verse presenting sexuality and femininity.I argue that the magazine’s pages demonstrate the iconic roles that Millay and Parker played in the cultural imagination. I use the advertisements and cartoons that variously picture and address the poets’ readers to analyze the kinship proposed between young single women working in the city and modern female poets writing about it. Both Millay and Parker were prominent writers of light verse, a genre found in newspapers and magazines and characterized by formal conventionality, simple diction, and (often) rollicking rhymes. This genre emblematized the energy and insouciance of youth culture, as well as the rebellion and flirtation of the flapper. The simplicity of the genre and its covert aggression—the punch-line or twist at the end of the poem—invited the common reader’s participation and indeed self-invention.

Poetry for Pleasure: Hallmark, Inc. and the Business of Emotion at Mid-Century

Poetry for Pleasure: Hallmark, Inc. and the Business of Emotion at Mid-Century by Melissa Girard

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

In the 1960s, Hallmark, Inc., purveyor of greeting cards, entered the book publishing industry. Their diverse offerings went far beyond mere gift books; throughout the decade, they issued a variety of highly readable anthologies focusing on Japanese haiku, African American poetry, popular love poems, limericks, and children’s verse, as well as canonical figures such as Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and T.S. Eliot. Hallmark’s capacious vision stood in stark contrast to their New Critical contemporaries, who, at mid-century, were overwhelmingly preoccupied with narrowing the poetic canon. At a moment when the literary academy had abandoned popular poetry and popular readers almost entirely, Hallmark preserved and fiercely defended what they termed a “democratic” poetics. “The way to read a poem is with an open mind, not an open dictionary,” the editors insist in the 1960 anthology Poetry for Pleasure.

My paper takes Hallmark’s poetics seriously as a democratic alternative to the elitism of the mid- century American academy. I am attentive not only to Hallmark’s poetry anthologies but also to their innovative marketing and advertising campaigns, which placed these attractively packaged and affordable books in supermarkets and drugstores. In so doing, I argue that Hallmark played a vitally important, populist role throughout the 1960s, advocating on behalf of poetry and actively attempting to broaden its readership. At the same time, my paper also explores the complex ramifications of Hallmark’s corporate sponsorship of poetry. While Hallmark undoubtedly empowered the average reader, they also sought to strengthen their brand and, concomitantly, to profit from Americans’ increasing poetic literacy. This “emotion marketing,” as Hallmark terms it, belies their “democratic” agenda. My paper recovers this largely forgotten historical struggle between the academy and corporate America for the hearts and minds of poetry readers.

My paper takes Hallmark’s poetics seriously as a democratic alternative to the elitism of the mid- century American academy. I am attentive not only to Hallmark’s poetry anthologies but also to their innovative marketing and advertising campaigns, which placed these attractively packaged and affordable books in supermarkets and drugstores. In so doing, I argue that Hallmark played a vitally important, populist role throughout the 1960s, advocating on behalf of poetry and actively attempting to broaden its readership. At the same time, my paper also explores the complex ramifications of Hallmark’s corporate sponsorship of poetry. While Hallmark undoubtedly empowered the average reader, they also sought to strengthen their brand and, concomitantly, to profit from Americans’ increasing poetic literacy. This “emotion marketing,” as Hallmark terms it, belies their “democratic” agenda. My paper recovers this largely forgotten historical struggle between the academy and corporate America for the hearts and minds of poetry readers. Poetry vs. Paris Hilton: Who’s On Top?

Poetry vs. Paris Hilton: Who’s On Top?by Angela Sorby

Marquette University

In 2007, Paris Hilton read a poem on Larry King Live that she had supposedly written in prison. The poem, which turned out to be plagiarized from a fan letter, prompted a media scandal that raises implicit questions about how poetry works, or fails to work, as a popular cultural medium. In Understanding Popular Culture, John Fiske argues that, to be popular, a text or commodity must be relevant: it must be functionally available to consumers who make it a meaningful part of their daily lives. In this essay, I will twist Fiske’s thesis to argue that poetry is a functional medium because people are not comfortable using it in their daily lives.

Through an analysis of the Paris Hilton poetry scandal, and of subsequent poems written to (and against) Hilton, I will suggest that precisely because poetry is not “relevant” to most consumers, it arouses strong reactions (disciplinary scorn, passionate defense) when it appears in mass cultural contexts. Poetry, in this case, prompts a breakdown in the ideological unity of an icon such as Paris Hilton, whose popular subjectivity relies on hyper-legibility and relevance.

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

"Put Readings on YouTube"

Here's the skinny on what's been happening literature-wise in Iowa City of late. After several years of application-making, bell-ringing, and horn-tooting, Iowa City was named a UNESCO "world city of literature," joining Edinburgh, Scotland, and Melbourne, Australia as the only other cities in the world with that designation. Check out the press release yourself here. Way to go, Iowa City.

Here's the skinny on what's been happening literature-wise in Iowa City of late. After several years of application-making, bell-ringing, and horn-tooting, Iowa City was named a UNESCO "world city of literature," joining Edinburgh, Scotland, and Melbourne, Australia as the only other cities in the world with that designation. Check out the press release yourself here. Way to go, Iowa City. At the same time, as it was becoming clear that Iowa City would indeed achieve "world city of literature" status, Iowa Public Radio announced that it would be dropping "Live From Prairie Lights" from its programming schedule. For as long as most people remember, "Live From Prairie Lights" has broadcast visiting poets and fiction writers reading, well, live from Prairie Lights Bookstore in downtown Iowa City. Apparently, though, a number of forces conspired to drive listeners away. The show's host was boring. The readers (like many readers) didn't perform their work with any particular flair. And the show ran once or twice on air which, as you and I both know, simply ain't gonna fly in an age of YouTube and podcasts. Are you gonna rearrange your schedule, wait until 8 pm, then tune in your crystal set to listen to a boring reading followed by an even more boring set of questions? "Poetry & Popular Culture" sure isn't.

At the same time, as it was becoming clear that Iowa City would indeed achieve "world city of literature" status, Iowa Public Radio announced that it would be dropping "Live From Prairie Lights" from its programming schedule. For as long as most people remember, "Live From Prairie Lights" has broadcast visiting poets and fiction writers reading, well, live from Prairie Lights Bookstore in downtown Iowa City. Apparently, though, a number of forces conspired to drive listeners away. The show's host was boring. The readers (like many readers) didn't perform their work with any particular flair. And the show ran once or twice on air which, as you and I both know, simply ain't gonna fly in an age of YouTube and podcasts. Are you gonna rearrange your schedule, wait until 8 pm, then tune in your crystal set to listen to a boring reading followed by an even more boring set of questions? "Poetry & Popular Culture" sure isn't. But the old-time codgers here in Iowa City—many of whom haven't listened to "Live From Prairie Lights" in ages (and many of whom would privately admit that the show actually is pretty boring)—have been lamenting the passing of the wireless torch and the demise of the radio show. How horrid, they say, that on the eve of being designated the world's third city of literature Iowa City should strip away its literary radio programming. Some heavies like former Iowa Poet Laureate and Writers' Workshop teacher Marvin Bell and current Iowa Poet Laureate Robert Dana have weighed in on the controversy.

But the old-time codgers here in Iowa City—many of whom haven't listened to "Live From Prairie Lights" in ages (and many of whom would privately admit that the show actually is pretty boring)—have been lamenting the passing of the wireless torch and the demise of the radio show. How horrid, they say, that on the eve of being designated the world's third city of literature Iowa City should strip away its literary radio programming. Some heavies like former Iowa Poet Laureate and Writers' Workshop teacher Marvin Bell and current Iowa Poet Laureate Robert Dana have weighed in on the controversy.And what follows is Mike Chasar's take on the topic, a view officially endorsed by "Poetry & Popular Culture."

Appeared in the Press-Citizen on November 25, 2008

Put Readings On YouTube

Congratulations, Iowa City, for being designated UNESCO's third City of Literature. Via the Iowa Writers' Workshop, the International Writing Program and other innovative and historically significant literary efforts, you have changed the way writing happens in the United States and around the world.

It is now time to remember that history, stop lamenting the disappearance of "Live from Prairie Lights" from Iowa Public Radio and seize on that disappearance as an opportunity to reimagine what such broadcasts might look and sound like in a digital age where podcasts and YouTube reach a much larger audience than WSUI and Julie Englander ever could.

Radio poetry history

Literature has long been a part of public and commercial radio programming. In the 1920s, poetry radio shows emerged as popular parts of the media landscape. Some shows -- like Ted Malone's "Between the Bookends" and Tony Wons's "R Yuh Listenin'?" -- were broadcast nationwide and had large, avid audiences who not only waited by their sets to hear poems read aloud to live organ music, but who flooded the studios with fan mail as well.

At the height of his popularity in the 1930s, Malone's show received more than 20,000 fan letters per month. Much as I hesitate to mention that other state university north of Ames, you can go there and read some of these fan letters yourself, which are now in the Arthur B. Church Papers in the Special Collections Department of that university's Parks Library.

Malone and Wons weren't the only ones to dazzle first generation radio audiences with poetry. A.M. Sullivan's "New Poetry Hour" on WOR (New York) strove to broadcast poetry of only the highest literary quality. Eve Merriam's Out of the Ivory Tower on WQXR (New York) featured Leftist poets reading their work. Ted Malone was known for showcasing "amateur" poetry sent in by his listeners, but he also read poetry by Shakespeare, Keats, W.B. Yeats and T.S. Eliot.

And on the eve of World War II -- when radio was the major source of up-to-the-moment news for many Americans -- NBC broadcast Edna St. Vincent Millay's book-length propaganda poem "The Murder of Lidice" to a nationwide audience of millions. It was performed by Hollywood actor and two-time Academy Award nominee Basil Rathbone and was accompanied by a chorus of singers. Not only was that broadcast shortwaved to England and Europe, but the poem was translated into Spanish and Portuguese and beamed to South America as well.

Finding today's audiences

Those days may be over, but audiences still await -- though they're not sitting in Prairie Lights, nor, apparently, are they sitting by their radios diligently tuning in to Iowa Public Radio.

Instead, they are online watching "The Daily Show" and Tina Fey impersonate Sarah Palin on YouTube. They are downloading podcasts. They tune in at their convenience, but they do so in enormous numbers.

"Live from Prairie Lights" should find a model in President-elect Barack Obama, who recently gave the weekly Democratic radio address not just on radio, but also for the first time on YouTube.

If, as one university official claimed, "Live from Praire Lights" is a "standard-bearer" for Iowa City's literary culture, then it should not be constrained by the time tables of either a bookstore or a public radio schedule. It should be recorded in video and audio formats. It should be posted online for listeners to access at their convenience -- at a coffee shop, at work, or even (anachronistic as it might sound) at a fireside.

The readings of Iowa City's writers and visiting writers should be posted on YouTube where people not just in Iowa City, but around the world, can access them. Imagine the global audiences who might tune in to hear participants in the International Writing Program read from their work.

If "Live from Prairie Lights" really is the "gem" that people say it is, then why not share that wealth with as many people as possible? That would not only be a move in keeping with Iowa City's leadership and innovation in arts and letters, but the mark of a true world city of literature as well.

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Pedestrian Poetry

A few weeks back, my friends over at Vowel Movers were crowing about a perfect pair of poetry pumps from Nine West that went perfectly with their Sylvia Plath dresses. Ever on the lookout for new and interesting footwear, "Poetry & Popular Culture" is happy to call attention here to the "Poetic License" brand line featuring lyrically trendy styles such as "Romance," "Tranquility," "Venom," and the "Breathless" Mary Jane pictured to the left. Hopefully now, Vowel Movers, you'll finally be able to work those Gertrude Stein slacks—or your Elizabeth Barrett Browning hoop skirt, or that Edna St. Vincent Millay twin-set, or even your Beowulfian bodice—into a complete outfit to take on the town. Carrie Bardshaw, eat your heart out.

A few weeks back, my friends over at Vowel Movers were crowing about a perfect pair of poetry pumps from Nine West that went perfectly with their Sylvia Plath dresses. Ever on the lookout for new and interesting footwear, "Poetry & Popular Culture" is happy to call attention here to the "Poetic License" brand line featuring lyrically trendy styles such as "Romance," "Tranquility," "Venom," and the "Breathless" Mary Jane pictured to the left. Hopefully now, Vowel Movers, you'll finally be able to work those Gertrude Stein slacks—or your Elizabeth Barrett Browning hoop skirt, or that Edna St. Vincent Millay twin-set, or even your Beowulfian bodice—into a complete outfit to take on the town. Carrie Bardshaw, eat your heart out. While "Poetry & Popular Culture" is hardly in the business of dispensing advice on matters sartorial, it nevertheless can offer a poetry pamphlet, "The Shoe Day of Judgment," in the way of a gentle cautionary tale. Produced in 1900 by the St. Louis Wertheimer-Swarts Shoe Company, manufacturers of Clover Brand Shoes (not Joshua Clover Brand Shoes), the pamphlet is a warning for those who might all-too-casually slip "Venom" or "Romance" onto their hoofers and go about their daily lives, wearing those shoes hither and thither, willy-nilly through sleet and snow and city and countryside with little consideration for the well-being, care, and feeding of the shoes themselves.

While "Poetry & Popular Culture" is hardly in the business of dispensing advice on matters sartorial, it nevertheless can offer a poetry pamphlet, "The Shoe Day of Judgment," in the way of a gentle cautionary tale. Produced in 1900 by the St. Louis Wertheimer-Swarts Shoe Company, manufacturers of Clover Brand Shoes (not Joshua Clover Brand Shoes), the pamphlet is a warning for those who might all-too-casually slip "Venom" or "Romance" onto their hoofers and go about their daily lives, wearing those shoes hither and thither, willy-nilly through sleet and snow and city and countryside with little consideration for the well-being, care, and feeding of the shoes themselves. "The Shoe Day of Judgment" begins with a short preface, "Abuse of Shoes," explaining the man- ufacturer's complaint and appealing for "some sense": too many people hold a shoemaker responsible not for flaws in workmanship but for the consumer's irresponsible misuse. "There is nothing," Wertheimer-Swarts proposes, "that clothes mankind so much abused, and yet is so unreasonably expected to continue Perfect in Fit, Style, Workmanship and Service, as are its Shoes. We appeal to a fair-minded, thinking public to give a few facts their consideration. No two persons wearing the same grade and make of shoes will realize the same service. Leather will wear out. Gritty soil, briars, rocky and rough surfaces, Scuff and Peel soft, velvety uppers. Fine mellow tannages of leather in footwear exposed to extremes of weather, to Heat and Cold, to Mud and Slush, will crack. Seams put to such tests Rip. Failure to care properly for your shoes, by frequent cleaning, oiling and dressing, exposes them to rapid destruction and decay."

"The Shoe Day of Judgment" begins with a short preface, "Abuse of Shoes," explaining the man- ufacturer's complaint and appealing for "some sense": too many people hold a shoemaker responsible not for flaws in workmanship but for the consumer's irresponsible misuse. "There is nothing," Wertheimer-Swarts proposes, "that clothes mankind so much abused, and yet is so unreasonably expected to continue Perfect in Fit, Style, Workmanship and Service, as are its Shoes. We appeal to a fair-minded, thinking public to give a few facts their consideration. No two persons wearing the same grade and make of shoes will realize the same service. Leather will wear out. Gritty soil, briars, rocky and rough surfaces, Scuff and Peel soft, velvety uppers. Fine mellow tannages of leather in footwear exposed to extremes of weather, to Heat and Cold, to Mud and Slush, will crack. Seams put to such tests Rip. Failure to care properly for your shoes, by frequent cleaning, oiling and dressing, exposes them to rapid destruction and decay." "Such abuses," the shoe company goes on, "are the burden of our song." And what a song it is! In 35 ballad stanzas, "The Shoe Day of Judgment" tells of a shoemaker who falls asleep and dreams of a day when shoe-abusers get their comeuppance for unfairly holding manufacturers responsible for every crack, rip, or tear caused by misuse. A farmer who puts his shoes against the fire and redeems them for a new pair the following day is sent to hell. A boy who tears his shoes on "gravel, brick and stone" is sentenced to twelve months of study without vacation. A teamster—not yet part of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters—has his "foolish head" soaked. Another man is sent to a thousand years in jail because he returned his shoes:

"Such abuses," the shoe company goes on, "are the burden of our song." And what a song it is! In 35 ballad stanzas, "The Shoe Day of Judgment" tells of a shoemaker who falls asleep and dreams of a day when shoe-abusers get their comeuppance for unfairly holding manufacturers responsible for every crack, rip, or tear caused by misuse. A farmer who puts his shoes against the fire and redeems them for a new pair the following day is sent to hell. A boy who tears his shoes on "gravel, brick and stone" is sentenced to twelve months of study without vacation. A teamster—not yet part of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters—has his "foolish head" soaked. Another man is sent to a thousand years in jail because he returned his shoes:I bought them small, I must confess,

To make my feet look smaller,

Yet soon returned them by express,

Marked 'C.O.D. $1.00.'"

While calling attention to the particular pleasure of rhyming "smaller" with "$1.00," "Poetry & Popular Culture" also wishes to direct attention to the similar fate of the maid, which may be of special interest to those smiling yet careless misses seeking out Nine West's Poetry pump or any of the Poetic License products currently on the market:

While calling attention to the particular pleasure of rhyming "smaller" with "$1.00," "Poetry & Popular Culture" also wishes to direct attention to the similar fate of the maid, which may be of special interest to those smiling yet careless misses seeking out Nine West's Poetry pump or any of the Poetic License products currently on the market:Then came a maid, a smiling miss,

Whose action naught condones,

Who careless ran, that way and this,

And walked on glass and stones.

Back to the dealer with an air

Of injured worth she went:

"I'll have to have another pair;

These are not worth a cent!"

Oh, when the Judge encountered this,

His mien was most severe.

"You'll have to go, my careless miss,

Barefooted for a year!"

While "The Shoe Day of Judgment" may be a harrowing tale, its use of poetry as both a tool for advertising and instruction in the consumer marketplace is not unusual, as virtually every product was hawked via verse at one time or another during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Back then, poems were employed for their prestige or entertainment values. Nowadays, though, at least to judge from Nine West and Poetic License, the title of Poetry is grafted directly onto the product itself, because what can be more reassuring in our uncertain age than knowing that what we buy—indeed, even the very act of buying—is where, in fact, the poetry's at.

While "The Shoe Day of Judgment" may be a harrowing tale, its use of poetry as both a tool for advertising and instruction in the consumer marketplace is not unusual, as virtually every product was hawked via verse at one time or another during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Back then, poems were employed for their prestige or entertainment values. Nowadays, though, at least to judge from Nine West and Poetic License, the title of Poetry is grafted directly onto the product itself, because what can be more reassuring in our uncertain age than knowing that what we buy—indeed, even the very act of buying—is where, in fact, the poetry's at.