When people refer to "carriers' addresses," they usually mean the 19th century New Year's poem-greetings delivered to people's doorsteps by newspaper printers' devils—apprentices who usually were not paid for their work—who were seeking a tip to help pay their room and board for the coming year. These were (typically) clever, sometimes fairly lengthy poems summarizing the previous year's events, often authored by the printers' devils themselves, and frequently ended with an appeal to the homeowner such as the following from an 1870 address "To the Patrons of The Daily Picayune" in New Orleans:

From the fulness of your cheer,

Give to him a little share,

To lighten burdens he must bear—

And may those blessings held most dear,

Be yours throughout the glad New Year,

Gladdening your days forever here,

the Carrier prays.

For more carriers' addresses, see the very nice exhibit hosted by Brown University at http://dl.lib.brown.edu/carriers/index.html. Also check out Leon Jackson's "We Won't Leave Until We Get Some: Reading the newsboy's New Year's address" at http://www.common-place.org/vol-08/no-02/reading/.

But in the 19th century, printers' devils weren't the only ones carrying poems around. Take, for example, the postcard reproduced above: "A Railroad Boy's Appeal." Crippled in an accident, the card's bearer is now selling his "song" to sympathetic passengers or passers-by. The poem concludes:

And now, dear friends, I'm as you see

Poor, helpless and alone;

No other way to buy a limb—

Will you please buy my song?

And may God bless you all,

This is my heart-felt-prayer;

And by-and-by may we all meet

In realms just over there.

Signed "C.E.H.," the postcard has a footer that reads "PRICE.—Whatever you wish to give."

In the more elaborate broadside pictured to the left, "The Wounded Soldier's Appeal," bearer David Gingry, Jr. relates how he was permanently wounded while fighting for the Confederate side in the Civil War. Lest there be any misinterpretation while reading the poem, however, the piece begins with a little prose testimony: "The undersigned, a brave soldier of the army of the Potomac, asks the aid of the people to enable him to support A WIFE AND FIVE CHILDREN, who have no other means of subsistence. He lost his left hand at Petersburg, besides being wounded in his other arm, in his right leg and in the head. Being so crippled, therefore, he is unable to do the day's work of an ordinary laboring man, and the only means left to him to make an honorable living is in selling the following original poem, which he hopes all will be kind enough to buy. He is commended to the generosity of the public generally."

That "original poem" reads, in part:

And, shot in arm, in leg, in head,

In that most fearful, bloody fray,

And left upon the field for dead,

Was he who asks your aid to-day.

But, thanks to God! he lives to see

His wife and children once again,

Though to that wife and children he

Is more a burthen than a gain.

His hand is gone; and thus to aid

Those loved ones in their day of trial,

He sells this little serenade,

And hopes to meet with no denial.

Printed in Altoona, Pennsylvania, the broadside is priced "Ten Cents Each Side." The reverse, in a humorous gesture at a little con, is blank.

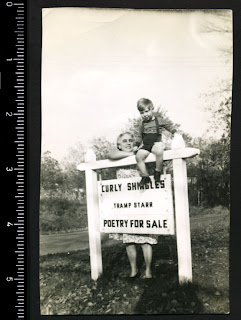

Both of these pieces are "carriers' addresses" of a different sort than the ones originating with newspapers; instead of recounting the events of the past year, they recount the bearer's story. Both types stand to remind us of the popular portability that poetry offered before the "slim volume" and "little magazine" became default media for poems. Is there an equivalent today?

Here's a hilarious excerpt from "In Hanuman's Hands: A Memoir of Recovery and Redemption" by Srinivas (Cheeni) Rao, in the process of being published by HarperOne (an imprint of HarperCollins) and soon to make its way to a bookstore near you:

Here's a hilarious excerpt from "In Hanuman's Hands: A Memoir of Recovery and Redemption" by Srinivas (Cheeni) Rao, in the process of being published by HarperOne (an imprint of HarperCollins) and soon to make its way to a bookstore near you: